What's In a Name? 10 Experts Weigh In on Incident Response Data Mining

Contents

When a cybersecurity event occurs and data is potentially compromised, that data must be assessed. A team of experts must comb through it for personal data (commonly called PII or PHI in the U.S.) and generate a list of affected people. Depending on a variety of factors including data types, number of people, and their geographic location, legal counsel can determine whether the event constitutes a breach and if notifications are required.

The need for this is relatively new, especially when compared with adjacent markets or cybersecurity as a whole. It took off when the EU announced the GDPR in 2016, which spawned a global focus on strengthening privacy protections and improving transparency when those protections fail.

This process is typically included within the broader forensics umbrella. Both share the same category on the NIST Cybersecurity Framework, classified together under Respond: Analysis (RS.AN). It’s known as an expensive part of incident response (IR), particularly among insurers. According to NetDiligence’s 2022 Cyber Claims Study, forensics (enveloping this process) made up more than half of crisis services costs over the past five years, averaging $52,000 per incident for SMEs.

Despite being such a significant expense in the IR process, industry experts are still working toward alignment on workflows, approach, and even the language used to describe it. To explore this, we spoke with leaders from four different groups in this space:

- Technical — Digital forensics & incident response (DFIR) groups or review & legal service providers who analyze potentially compromised data. These are also the people who use Canopy’s Data Breach Response software.

- Legal — In-house or outside counsel who assess the technical teams’ findings and make breach & notification determinations.

- Insurance — Often the drivers of the whole process, insurers are highly influential in selecting providers, and they pay for all of the above.

- Consulting — Experts who advise companies on strategies and tactics, both proactively and in response to an incident.

Canopy falls within a fifth category: Technology. We provide AI-powered software that enables service providers to accomplish the process discussed in this post.

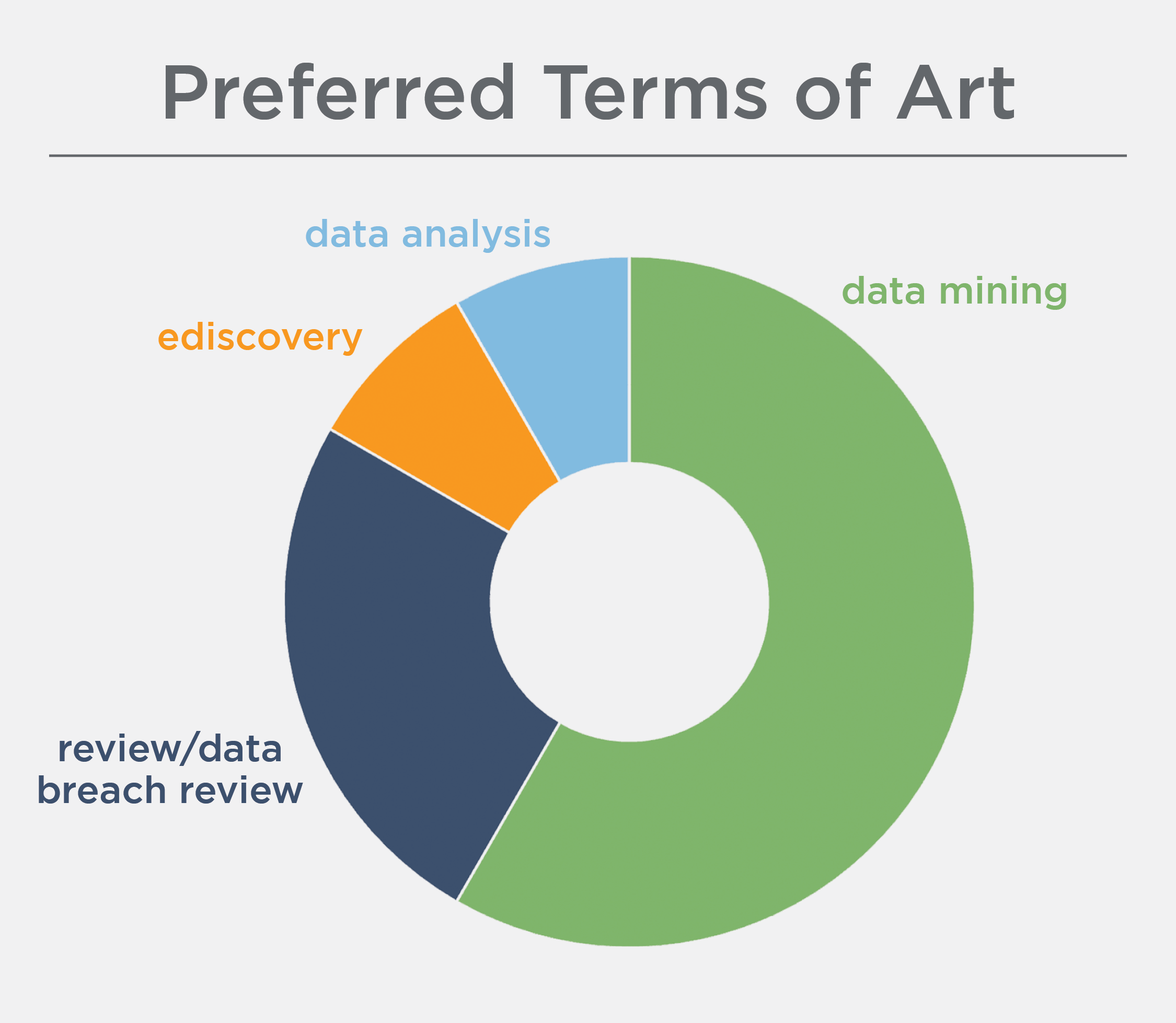

The Top Term of Art: Data Mining

Of the 10 people we interviewed, the majority preferred the term “data mining” to describe either the entire process or a subset of it. Why? John Spiehs, Head of Claims at Converge Insurance, summed it up: “We don’t overthink it — we just use the term of art that most of the industry uses.”

“I hear the term ‘data mining’ the most — it’s a fancy term for doc review,” said Max Perkins, Head of Strategy and Innovation at AXIS Capital.

On the technical side, KLDiscovery also calls the broader process “data mining.” “Specific to incident response, it’s the process of identifying potentially impacted entities and the sensitive data points related to each entity,” said Eric Robinson, Vice President, Global Advisory Services & Strategic Client Solutions.

“It’s kind of a silly term of art, but it wasn’t invented by me,” said James Manari, Vice President of Sales at DWF (formerly Mindcrest). Of note is that unlike others who prefer the term data mining, James and his team use it to refer to a subset of this process — specifically PII/PHI identification, not encompassing review and consolidation.

“I’m very clear about bifurcating it so that we can show exactly how PII detection accuracy affects the review cost,” James added. “Sometimes I specify ‘AI-assisted data mining’ to distinguish between ediscovery and what Canopy does, which far exceeds just typing words into a search box.”

“I’ve heard people use ‘PII Audit,’ but we try to stay away from terms that sound more ediscovery-ish, because it’s really not ediscovery.”

This terminology is taking root in the legal world, too. “I’ve been doing this for more than 13 years, and I use the term ‘data mining’ because that’s what we’re doing — mining the documents for data,” said Melissa Ventrone, Partner at Clark Hill. Like James, she is also intentional about differentiating from ediscovery. “I’ve heard people use ‘PII Audit,’ but we try to stay away from terms that sound more ediscovery-ish, because it’s really not ediscovery.”

The Data Mining vs Ediscovery Controversy

There was an overwhelming trend among interviewees toward delineating between this process and ediscovery, with other industry leaders aligning with Melissa on challenging the synonymous use of these terms.

“The problem that I personally have with ‘ediscovery’ is that it has a broader context,” said Max. “Whereas I tend to think of data mining as looking at a specific set, trying to weed out false positives and false negatives.”

“‘Ediscovery’ is the baseline catch-all when it comes to document review because it can incorporate anything having to do with ‘discovery,’ including the discovery of PII,” added Eric. “But the approach to data mining is unique enough that it deserves its own subset.”

Not everyone has accepted “data mining” as the best label for this process. While Michael Borgia, Partner & Information Security Practice Lead at Davis Wright Tremaine, agrees that this process is unique, he continues to call it “ediscovery” because, he says, the industry hasn’t offered up a better option. “‘Discovery’ refers to a specific litigation process that ends with making privilege calls, so it’s not the same. But when the need for this arose, there were no other tools that could take large amounts of data, process them, and run searches through them, so the two markets got intermingled.”

“I see two main issues with the term ‘data mining,’” Michael added. “First, it can mean lots of different things — not just this. Second, it has some negative connotations and can scare clients. It makes them envision a process that’s chaotic, expensive, and incredibly time-consuming. Not to minimize the work, because it is niche and requires expertise; but it’s a very defined, organized process for the experts in this field.”

Taking a Client-Centric Approach

Whether coming from the technical, legal, insurance, or consulting side, service providers are deeply engaged in all the ins and outs of this space. But dealing with a cyber incident is particularly stressful for the end client, so their comfort and understanding are paramount. Michael isn’t the only expert we spoke with who had chosen their terminology with the client in mind.

Allison J. Bender, Partner at Dentons, agreed that while she sometimes uses “data mining” (especially internally, because it’s so widely understood in the industry), it can be triggering for her clients. “They often have negative connotations associated with that term and its ties to the collection of consumer data,” she said. “That’s why I tend to use ‘data analysis’ with clients, to avoid any potential sensitivities.”

While potential preconceived notions about “data mining” don’t deter her from using that term, Melissa takes time to define it in more generic language for clients, especially ones who haven’t been through this process before. “I just explain what it means: that we’re identifying personal data elements to determine your notification obligations,” she said.

Along the same lines, Eric added: “There are some very sophisticated law firms and breach coaches that understand this and take a leading role in guiding the client. But if we’re working directly with the end client, we use our standardized verbiage — ‘data mining’ — and just explain as needed so that they understand what’s happening.”

The team at Asceris discussed this potential communication barrier early on, and they decided to use two different terms depending on their audience. “We use ‘data breach review’ with clients, and explain that we’re basically looking for who the affected individuals are that may need to be notified — whose personal data has been accessed,” said Anthony Hess, CEO.

“We still talk about ‘data mining’ with insurers and law firms because it’s so prevalent in the industry, so we use their preferred terminology,” added Neil Meikle, CTO at Asceris. “But ultimately, our end clients are the companies that have been breached, and we wanted a term that best described what we’re doing in plain English.”

Other Terms-of-Concern

None of the experts we interviewed referred to this process as “data breach response” or “incident response”, but a few had heard these terms used by colleagues or others in the industry. The overarching feedback was unfavorable.

“Breach response is extremely broad,” said Michael. “I do ‘breach response’ because I advise clients on responding to a breach. Forensics firms do ‘breach response’ in terms of investigating, getting a sense of what happened, and advising locking down a system from a technical standpoint. So it’s confusing because people have different interpretations of what that means.”

“I’ve also heard ‘data breach response,’ but that can include more parts,” Anthony agreed. “It’s too broad to just refer to this.”

Violet Sullivan, CIPP/US, Vice President of Client Engagement at Redpoint Cybersecurity, also finds it to be potentially problematic. “I often see data mining vendors calling themselves ‘incident response,’ which is very broad — we’re all incident response,” she said. “You don’t want to be perceived as a competitor when you can actually help another group.”

"I often see data mining vendors calling themselves ‘incident response,’ which is very broad — we’re all incident response."

Regarding data breach response, Violet added: “That term can create tension with legal counsel, because they are ultimately the ones who make that breach determination. They don’t want data companies or technical groups making that call or inserting legal decisions.”

A Period of Evolution

These conflicting views on language may be indicative of broader disarray among the key groups involved in this process, extending outside of terminology into core aspects like approach, workflows, and technology. But that is beginning to shift.

As the organizations paying the bill, insurers orchestrate this process and bring the other groups together. “First we pull in a data mining provider to scan for regulatory or statutory protected data, find out how many people are affected, and where those people live,” said John. “Then we work with legal counsel to determine if a threshold is met to require notifications.”

Thus, insurers are in a prime position to drive structural change. “We’re at the center of all of these claims, so we can see the best practices that lead to the best results,” said Max. But he has witnessed a steady inflation in the cost associated with this process. “One troubling area for cyber specifically is the lack of a feedback loop between the DFIR firms, the law firms, and the underwriting side. The broader insurance world is constantly moving to improve efficiency — and ultimately lower cost to the insured — based on the data they get back from claims investigations, but we don’t have a system for that right now in cyber.”

Some technical folks are working directly with insurers and law firms to initiate change. KLDiscovery began doing this type of work in 2013 using the tech that they know and love for ediscovery, because it was the best available option at that time. “We got to a place where we were able to do this work as effectively and efficiently as possible with those tools, but ediscovery platforms just weren’t built to do data mining work,” said Eric. “So we started using Canopy in 2020, and it allows us to bring a far more effective solution. We approach this from a holistic perspective — how do we get clients from A to Z most efficiently, most effectively, most accurately, at the lowest possible cost.”

"Ediscovery platforms just weren’t built to do data mining work. So we started using Canopy in 2020, and it allows us to bring a far more effective solution."

The team at Mindcrest has also been working to inform insurers about the process so they understand the effect that a provider’s approach and technology can have on overall cost. “I try to be very upfront about each component’s cost,” said James, noting that competitors using old-school strategies and tools will often submit lowest-possible quotes to get a foot in the door. “This might seem cheaper initially, but it often results in time and cost adjustments based on the density of the data, monstrous spreadsheets — insert reason here — because they didn’t have any idea what they were dealing with when they quoted. With Canopy, it’s hard for us to be surprised.”

This evolved approach can take some time to get used to, but Asceris sees the industry moving in the right direction. “In the past, the client’s law firm would give us a list of keywords to search for and we’d have to review all of the keyword matches. With Canopy, we have a lot more power to find personal data,” added Neil. “It’s a shift away from the traditional approach; we just have to explain why we do things differently and show counsel the new levers that they now have control over.”

And on the legal side, counsel is becoming more open to leveraging AI for this work — and seeing the difference. “The bottom line is, human review really isn’t that good,” said Michael. “But that doesn’t get a lot of attention because it’s the norm. It’s like when you see an article about an autonomous vehicle getting in a crash, and people react with, ‘Oh, that’s not safe!’ But have you seen how people drive? The goal shouldn’t be perfection, it should be ‘better than what people can do.’”

So, What’s In a Name?

Among the interviews we conducted for this post, “data mining” is the most popular term used to describe this process, and everyone was familiar with it. But there wasn’t an overwhelming consensus that it was the best choice. Many also agreed that another term or different language would be useful for external client- or public-facing communications. For now, it seems that each group, each company, and even each individual within each company are using their own preferred terminology.

Names are powerful. They’re often the first thing you learn about someone or something. They provide an identity and, as shown in these responses, they trigger quick judgments, preconceived notions, and assumptions that can be difficult to overcome. Giving something a name can also unite people and allow them to organize around a shared passion, interest, or occupation.

Every person quoted in this article is associated with the same overall process, yet they have different or sometimes even contradictory names for what they do. We’re seeing a big shift right now as this relatively new industry establishes itself in the broader incident response space, and progress in communication among the four key groups: technical, legal, insurance, and consulting. It’s possible that if we can all align on, in Max’s words, “whatever the heck you want to call this,” then alignment in other areas — such as process, approach, workflows, and cost — will follow.

To that point, we at Canopy are reevaluating the terminology we use based on the insights gleaned from these interviews. We have referred to this process as “data breach response” until now, and we’ll continue to do so with the general public as it’s an easy concept for people outside of our industry to understand. But given the valid concerns expressed here about the legal perceptions of that term and the prevailing use of “data mining” among this group of experts, we will be making a shift in how we communicate within the IR industry. And linguistics aside, we’ll keep delivering efficiencies to the data mining process along the way.